Social Mobility—the Forgotten Dimension of Workplace Diversity

Social mobility continues to be a forgotten aspect of the DEIBA debate. Read what organizations need to consider to improve social mobility for a more productive workforce.

Share

Social mobility is a topic of high debate in the media, education system, and in policy-making across the world. Yet it does not always make its way into businesses and HR strategies in an impactful way. Perhaps because it is difficult to understand the business ROI of restricted social mobility in the workplace. And critically, it is not clear how a business can take action to improve social mobility.

What is social mobility?

So, what is social mobility, and why must it become as much a part of an organization's talent strategy as mainstream Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Belonging, and Accessibility (DEIBA)? Social mobility is:

‘The movement of individuals, families, households or other categories of people within or between social strata in a society. It is a change in social status relative to one's current social location within a given society’

In real terms, this means that the individuals born into low-income families do not have the opportunities in education, career, and life more broadly as those born into more privileged families, regardless of their talent and hard work—talk about an untapped talent pool of the future! And we see the gap growing from birth into adulthood; at age 3 poorer children are estimated to be, on average, nine months behind children from more wealthy families. And this trajectory continues—in the UK, Deloitte found that 51% of top medics, 54% of FTSE-100 CEOs, and 70% of High Court judges went to an independent school, compared to a tiny 7% of the population.

This is a global problem—nearly all major economies need to bridge their social mobility gap. The Nordics and parts of Europe tend to consistently outperform the rest of the world in terms of social mobility, but there are large differences between individual countries. Denmark, for example, is top of the Global Social Mobility Ranking index (2020), with Germany and France ranking 11th and 12 respectively, Singapore comes in 20th, marginally ahead of the UK (21st) and New Zealand (22nd). The United States is ranked 27th ahead of China (45th) Brazil (60th) and India and South Africa are ranked 76th and 77th respectively.

So, the problem is global, complex, and will require dedicated action across the board. Over the last few years, we have seen the focus on DEIBA enhance hugely. There has clearly been a strong societal movement towards this, and organizations have also realized that there are real dividends that come with diversity. In research highlighted by McKinsey (2018), companies that were in the top quartile for gender diversity on their executive teams, were 21% more likely to have above-average profitability than those companies in the bottom quartile. The respective figure for ethnic/cultural diversity was even bigger at 33%.

Denmark is top of the Global Social Mobility Ranking index (2020), with Germany and France ranking 11th and 12 respectively, Singapore comes in 20th, marginally ahead of the UK (21st) and New Zealand (22nd). The United States is ranked 27th ahead of China (45th) Brazil (60th) and India and South Africa stay ranked 76th and 77th respectively.

What are the consequences of restricted social mobility?

Social mobility is an aspect of the DEIBA debate which has had less focus, probably because it is seen as being more complex to evaluate and measure. Yet, there are real consequences associated with restricted social mobility. In a 2021 Harvard Business Review article about the forgotten dimension of diversity, it was reported that US workers from lower social class origins were 32% less likely to become managers than people from higher social class origins. And yet research continues to demonstrate that this type of diversity is good for business. A BCG study found that companies with more diverse management teams have 19% higher revenues due to innovation. This is because, within social diversity, we often see greater cognitive diversity—the inclusion of people with varying ways of thinking, different viewpoints, perspectives, and skill sets, i.e., people who do not ‘think alike’.

The business case continues when we cast our attention on the current operating climate and tight labor conditions. It is expected that by 2030 more than 85 million jobs could go unfilled because there are not enough skilled workers to take them. That is estimated to be an $8.5 trillion problem! By improving social mobility, organizations can open up a largely untapped talent pool.

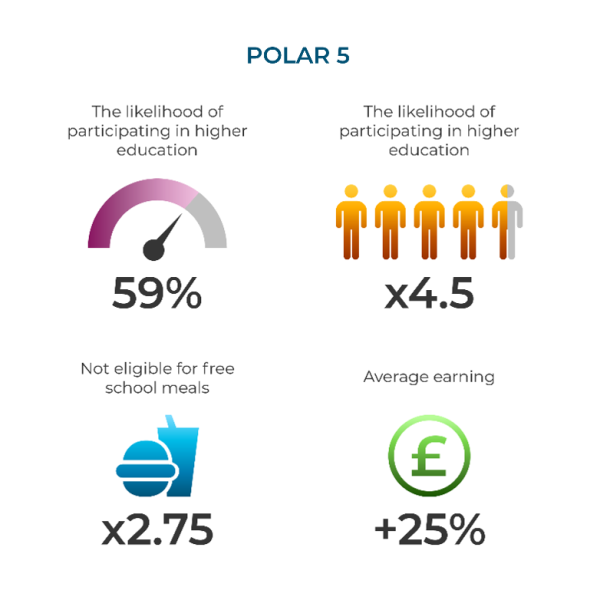

Research by Paul Bolton found that in the UK, 29% of individuals from POLAR group 1 enter into higher education compared to 59% of those in POLAR group 5. POLAR is Participation of Local Areas, which shows how likely young people are to participate in higher education across the UK. Areas with the lowest participation are referred to as POLAR group 1, with POLAR 5 being the highest.

And if you are in POLAR 5, you are 4.5 times more likely to attend a high tariff higher educational institution – those that require the most UCAS (Universities and Colleges Admissions Service) points – than if you are in the POLAR 1 group.

We find something similar if we look at other metrics of deprivation such as free school meals, where those who were not eligible for free school meals were 2.75 times more likely to attend a high-tariff educational institution, than those who were eligible for free school meals.

This has a knock-on effect on several variables, for example, subsequent earnings. In the same research, we find that those in POLAR group 5 were earning on average 25% more than those in POLAR group 1.

But does being from a socially disadvantaged background or, having less ease of access to high-status education mean you automatically have less capability or potential? In this very interesting report, they found that 28% of Business Operations and Management Specialists were STARS (Skilled Through Alternative Routes), yet 88% of job postings for those roles required a degree. So, by requiring a degree qualification, organizations are screening out a large population of individuals who could be successful in these roles.

The report also highlights that many STARS have the skills (e.g. active listening, persuasiveness, service orientation, critical thinking) to do higher-paid jobs.

However, mindsets about what employers think make a great employee coupled with a reliance on sourcing candidates, from quite a limited band of high-tariff academic institutions, e.g., an elite group of universities, means that organizations are missing out on the opportunity to hire from a more diverse and potential wise, very rich source of talent.

What are things organizations can do to enhance social mobility?

Expand the recruitment net – we know the economic impact that diversity can bring to an organization, so broaden the pool of potential candidates you can select from.

Things to consider:

- Is your candidate attraction strategy future-proofed and aligned with where the organization wants to go? In a world of disruption and uncertainty, are you attracting the diversity of talent which will enable you to remain agile and resilient? Can they critically evaluate and seize opportunities, but also demonstrate social perceptiveness in terms of empathy, inclusion, and emotional intelligence?

- Review the messaging your organization presents to candidates. Is your employee value proposition unconsciously putting up barriers, that may dissuade a broader candidate pool from applying to your organization? How might individuals from a range of backgrounds interpret your messaging? Are those types of individuals, for example, represented in employee stories on your website?

- Where do you source candidates? Do you tend to recruit from the same universities? Are there options to offer other routes into the organization, for example, apprenticeships, non–graduate routes, or paid internships?

- Insight and data. Review your talent acquisition data. Explore the trends and potential for adverse impact and understand the profile of an individual that is applying to your organization compared to those that are hired. Social mobility can be more challenging to measure, but you can access POLAR information at OFS (Office for Students) and UK.Gov.

- Focus on ability and potential. We probably all know the quote ‘Talent is everywhere, opportunity isn’t’, a focus on potential enables organizations to target the former.

- Use an assessment approach that is focused on understanding an individual’s potential. Someone from a disadvantaged background may not have had the opportunity to develop the ‘social capital’, that others may have had access to, but they could have the potential to be a great strategic thinker.

- Review your assessment process. Steps to make it more of an even playing field might include – offering advice on interview preparation. Ensuring your interviewers are fully trained, up to speed on best practices, and focused on evaluating behaviors rather than other ‘social cues’ that may disadvantage individuals from particular backgrounds.

- Review what will define success for the future. Are the behaviors and skills you have looked for hitherto, the ones that will be critical to delivering success for the future?

- Use insight and data to support your own people talent strategy. Having greater transparency of your own talent data will help understand where the strength of potential is to leverage. What are the development gaps that need closing? It will also help you identify those ‘hidden gems’. Those individuals who for some of the reasons discussed in this blog, may have fallen under the radar, but could be fabulous assets for the organization.

- Leverage internal mobility to upskill and progress employees. Having insight provides an opportunity to target the skills enhancement that will enable employees to grow and progress. Use pathways to highlight the different routes an individual can take to achieve a career goal—role moves provide those opportunities for individuals to gather skills and experience.

- Develop people internally as opposed to buying in skills/degrees. Leverage insight to focus development activity. If there is a requirement to build capability longer-term capability in digital literacy, focus on that as a strategic training aim. Mentoring has been highlighted as a key factor in supporting employees from disadvantaged groups.

Get insights into your internal talent with SHL Mobilize Solution. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.